Principle is All You've Got

Free expression is merely an abstract concept--and that's just the point

Probably the most widely admired definition and dissection of “cancel culture” remains Ross Douthat’s New York Times column, “10 Theses on Cancel Culture”—an article that, upon its publication in 2020, the cognoscenti immediately certified as the smart take on the subject. The most conservative of the Grey Lady’s columnists, Douthat is a decidedly minority taste among the paper’s readership, and his column rarely wins general accolades. But with this on-the-one-hand-on-the-other piece, Douthat manages, uncharacteristically, to create a broad and mushy middle ground, one composed of both cautious critics and those who defend at least some aspects of cancel culture. You should smell a rat.

In enunciating his theses, Douthat strives for a consensus-building moderation and deploys a posture of mollifying, seemingly bracing realism. Two interrelated theses define his argument, and both have been lauded by defenders of “cancel culture” as important concessions to their way of thinking – as indeed they are:

All cultures cancel; the question is for what, how widely and through what means. There is no human society where you can say or do anything you like and expect to keep your reputation and your job . . . Today, almost all critics of cancel culture have some line they draw, some figure – usually a racist or anti-Semite – that they would cancel, too. And [those] who criticise cancel culture, especially, have to acknowledge that we’re partly just disagreeing with today’s list of cancellation-worthy sins.

If you oppose left-wing cancel culture, appeals to liberalism and free speech aren’t enough . . . debates about cancellations are also inevitably debates about liberalism and its limits. But to defend a liberal position in these arguments you need more than just a defense of free speech in the abstract; you need to defend free speech for the sake of some important, true idea. General principles are well and good, but if you can’t champion controversial ideas on their own merits, no merely procedural argument for granting them a platform will sustain itself against a passionate, morally confident attack. So liberals or centrists who fear the left-wing zeal for cancellation need a counter argument that doesn’t rest on right-to-be-wrong principles alone. They need to identify the places where they think the new left-wing norms aren’t merely too censorious but simply wrong, and fight the battle there, on substance as well as liberal principle.

As one wokeish Twitterer nicely summarised Douthat’s position: “I didn’t think it’d be Ross Fucking Douthat who’d be the one at the NYT to articulate how “cancel culture” isn’t new per se, it’s just a shifting of moral expectations for public behaviour, and maybe centrists need an actual argument.” The Tweeterer’s approval is justified. Taken together, Douthat’s conciliatory arguments constitute an assault on the defense of free expression, a defense that can only be made along absolutist and abstract lines.

The faux-realism that insists that, come-off-it-everyone-draws-a-line-somewhere-when-it-comes-to-opinions-that-deserve-to-be-barred-and-punished is specious. It conflates those who favour licensed speech with those committed to free speech. The latter know that a liberal society and true freedom of thought can only survive if, within the law, no lines are drawn. They know that such a stance requires not, as Douthat would have it, the defense of those who avow opinions deemed “important” and “true” (who, by the very nature of their opinions, will be safe). Rather, it requires the defense of those who avow opinions known by all who matter to be reprehensible and dangerous – a category that emphatically includes the champions of racist or anti-Semitic opinions. And those really committed to free speech know that such a defense can only be mounted not, as Douthat declares, according to the “substance” of the opinion but as an assertion of general principle. Finally, they know that such an assertion is indeed (pace Douthat) a “passionate, morally confident” defense.

To indulge in the idea that those who decry today’s cancel culture do so merely because they don’t agree with “today’s list of cancellation-worthy sins,” and to acquiesce in ad hoc judgments about what views deserve to be defended from cancellation, is to succumb to historical myopia. It is to forget, as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, put it, “that time has upset many fighting faiths.” After all, the witch-hunts of the past weren’t led by those intent on doing bad (as the current comic-book version of history insists) but by those fervently committed to morality, not a few of whom incidentally believed that they were serving a politically progressive cause.

Today, people who would cancel those they deem racist, homophobic, xenophobic, etc, know that they are merely seeking to exclude from polite society and to drive from employment those who advocate morally repugnant ideas. People who campaigned successfully to cancel (to use an anachronistic term) pacificists, Communists, socialists, atheists, supporters of the ACLU and the NAACP, advocates of abolishing miscegenation laws, champions of labour unions, proponents of gay rights and of women’s access to contraception possessed the same moral clarity. A liberal and self-critical society can only function as such if it eschews the universal temptation to persecute people for their opinions, which means – as much as Douthat’s thoughtful social conservatism may shrink from the injunction – that it must apply to non-constitutional matters Justice Lewis Powell’s intellectually and morally laissez-faire proposition that “under the First Amendment there is no such thing as a false idea” (to quote the majority opinion in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc.).

Douthat’s own assertions demonstrate that no other approach can work. On the one hand, he’s apparently comfortable with what he sees as the consensus that a “racist or anti-Semite” can be hounded from his or her job. Opponents of cancellation, Douthat argues, shouldn’t defend those who hold such bad opinions; they ought to limit their efforts to defending “some important, true idea”—and they should accordingly limit criticism of censoriousness to those occasions when the censors’ opinions are “simply wrong.” But of course, there’s no fixed understanding of what constitutes racism or anti-Semitism. For example, where, precisely, is the line to be drawn between anti-Semitism and criticism, even dislike, of Israel? A particularly pernicious feature of today’s censorious thinking is its sweeping ambit for what counts as “racism,” “sexism,” “transphobia,” “Islamophobia,” “white supremacy,” and “xenophobia” (and for that matter, the Right’s bugbear, “Critical Race Theory”) – a development exacerbated by the equally vague, all-embracing notions of “dog whistle” and “harmful” speech (a point Douthat notes, even as he bafflingly fails to grasp its implications). Which people judged “racist” and “white supremacist” is it OK to defenestrate? For instance, staff members of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art drove out the senior curator of painting and sculpture, Gary Garrels, for saying that “it is important that we do not exclude consideration of the art of white men,” because to do so would amount to “reverse discrimination.” They judged his statement to be “white supremacist and racist.” To others, though, Garrels expressed an “important, true idea.” The logic of Douthat’s position would be to sanction Garrel’s expulsion because, after all, as he sees it, most of us draw the line at racism. But who’s to define that particular taboo? Although Douthat dismisses “general principles” as “all well and good,” in fact the only way out of the conundrum that the Garrels case poses is to defend the principle, not the specific idea that has roused the witch-hunters.

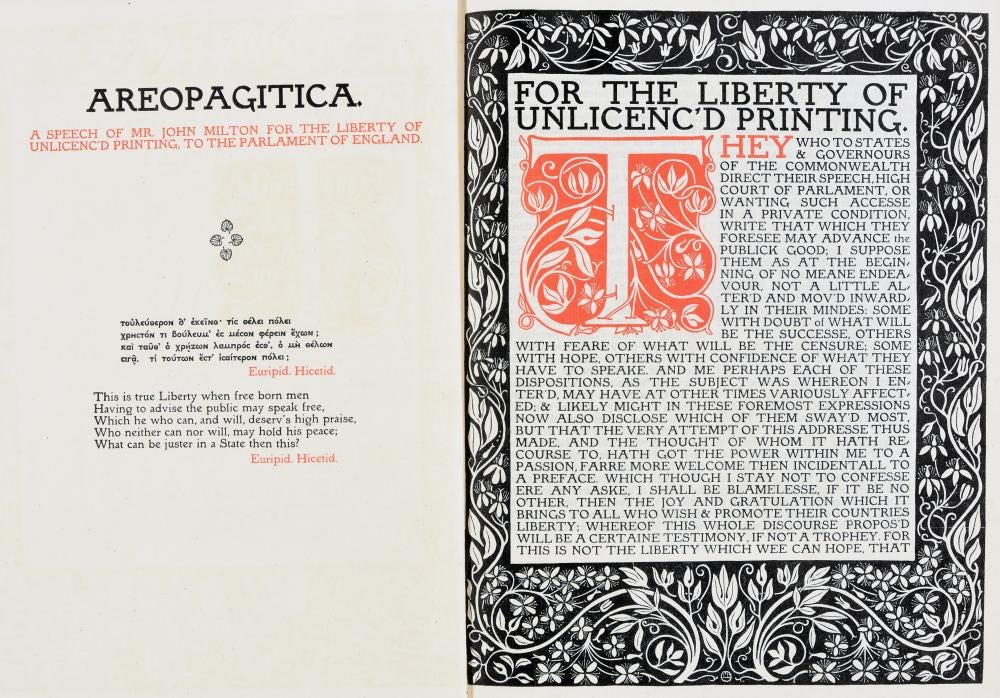

No, this doesn’t mean that ideas and opinions ought not to be vigorously challenged. It simply means that a mature, liberal people should insist that their society and culture draw a distinction between contesting the idea and hounding the promulgator of that idea from the public square and from his or her job, regardless of how repellant a few people or even most people find that idea. Free speech isn’t just a general principle; it’s a hard discipline. To Douthat, the repression and punishment of ideas by public opinion is largely just a matter of shifts in public opinion: we all do it. It’s relative and contextual. In fact, however, the defense of free speech is an absolute or it is nothing. The protection a society affords to those who espouse ideas cannot be applied according to the degree that society finds those ideas acceptable. To do so would assure a dangerous, or at best stultifying, conformity to mass or vociferous opinion. To Douthat, the proposition that people should be free to express unpopular or despised thoughts without risking their livelihoods seems “merely procedural” and nothing more than an abstract and bloodless concept. Surely it is. But to civilised and tolerant people (a group that assuredly includes Douthat), the ideas in Areopagitica, On Liberty, and the (mostly) glorious tradition of American free-speech jurisprudence – all based solely on abstract principle, on what Holmes acknowledged to be merely “a theory” – are eminently worthy of battle in their defense.

_____________

A version of this essay was published in spiked.

"...the defense of free speech is an absolute or it is nothing. The protection a society affords to those who espouse ideas cannot be applied according to the degree that society finds those ideas acceptable. To do so would assure a dangerous, or at best stultifying, conformity to mass or vociferous opinion."

Thank you for this, it is very essential work.