In recent years, Americans have increasingly confused the right to free speech with a supposed right to disrupt and shout down the speech of others—speech they deem harmful, dangerous, or otherwise intolerable. This likening of speech to harm and danger puts society dreadfully close to viewing speech as an invitation to physical confrontation, like an old-fashioned gang fight. One side marshals its members and shows up heavy, aiming to put members of the other side to rout, not through force of argument (i.e., suasion) but through sheer verbal force (i.e., volume). Sometimes such confrontation actually does become physical.

This recent trend got its start when generally progressive students at some of the country’s most elite colleges and law schools began disrupting the scheduled appearances of public figures who had been invited to speak by other students at the respective schools. These public figures, as indicated above, were deemed to be trafficking in harmful, dangerous (right-wing) ideas and therefore needed to be silenced—not just protested, not just debated: silenced. More recently, generally conservative suburban parents have gotten in on the act, using similarly disruptive tactics to break up school-board meetings in protest of (left-wing) school policies relating to everything from mask mandates to transgender accommodations to the teaching of critical race theory.

We don’t normally associate hooliganism with suburban parents and privileged, elite college students, yet there they are on the inevitable cell-phone videos that emerge from these events, banging on tables, chanting loudly over the proceedings, shouting out physical threats, raising their middle fingers, and letting obscenities fly.

We’ve been here before, alas.

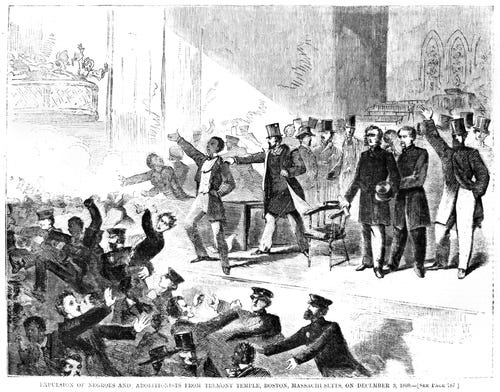

In early December of 1860, mere weeks after the election of Abraham Lincoln and mere months before the start of the American Civil War, Frederick Douglass and a group of abolitionists endeavored to hold a public meeting in Boston on the subject of how to end slavery in America. The meeting, somewhat pointedly, was scheduled to occur near the one-year anniversary of the death of the radical abolitionist John Brown. Even in the North, however, opinion on the matter of slavery (or at least on the matter of how vigorously its abolition should be pursued and at what cost to national unity) was divided. A mob descended on the meeting hall, shouted down the would-be speakers, and overran the stage. Municipal authorities, who had been derelict in forestalling the chaos, eventually dispersed the entire crowd (speakers and protesters alike). The meeting was thus broken up before it ever really got started. It was a classic case of the heckler’s veto at work, and of the heckler’s veto being allowed to work by passive authority figures (the mayor and the police, in this case) whose responsibility it was (and is) to ensure that the fundamental American right to free speech is not curtailed or denied by inflamed mobs, no matter how sure those mobs are of their own righteousness.

Like today’s wilding parents and college students, the people who broke up the abolitionist meeting were otherwise pillars of society, defenders of law and order, presumed exemplars of public spiritedness and the common good. During a now landmark speech at Boston’s Music Hall a week later, Douglass (an escaped slave turned statesman) remarked, “These gentleman brought their respect for the law with them and proclaimed it loudly while in the very act of breaking the law.” Apropos the pretensions of this group of upstanding citizens, he added: “when gentlemen approach us in the character of lawless and abandoned loafers,—assuming for the moment their manners and tempers,—they have themselves to blame if they are estimated below their quality.”

But Douglass’s indictment wasn’t just one of privilege run amok. “There can be no right of speech,” he avowed, “where any man, however lifted up, or however humble, however young, or however old, is overawed by force, and compelled to suppress his honest sentiments.” Furthermore, Douglass argued that the violation is twofold, victimizing not just the speaker but the would-be listener: “Equally clear is the right to hear. To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker. It is just as criminal to rob a man of his right to speak and hear as it would be to rob him of his money.”

However, following immediately upon that observation, he slyly acknowledged that by allowing the gentlemen-hecklers to carry the day, the Boston mayor and police force had, in essence, privileged the hecklers’ dissent (that is, the hecklers’ right to speak) over his and his fellow abolitionists’ right to speak: “When a man is allowed to speak because he is rich and powerful, it aggravates the crime of denying the right to the poor and humble.” Such an act of omission on the part of state authorities verges on a tacit, state-sanctioned suppression of speech, achieved through the unopposed violations of nonstate actors. Thus is the First Amendment violated in spirit—in principle—if not in a narrowly legal sense.

Progressives and moral reformers, Douglass argued, should be those most enthusiastic about the right of free speech, since it is “the great moral renovator of society and government.” Accordingly, that same right, per Douglass, “is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power.” Furthermore, the exercise of tyranny—which thinkers such as Edmund Burke and John Stuart Mill understood as well as Douglass—is not limited to exalted individuals possessed of inordinate political power. Tyranny can be practiced just as effectively, if not more effectively, by inflamed, self-righteous mobs and the societies (and governments) that tolerate them. “The tyranny of a multitude,” Burke noted, “is a multiplied tyranny.” Further still, it is a tyranny, per Mill, that is potentially more insidious, because “when society is itself the tyrant . . . its means of tyrannising are not restricted to the acts which it may do by the hands of its political functionaries.” Not only is social tyranny not limited to political means, it is also not subject to constitutional constraints on the exercise of political power. The victims of society’s suppression of speech are therefore left without constitutional remedy.

Thus is speech silenced without there being any direct violation of the First Amendment. Yet when we allow a speaker to be overawed by force, we effectively nullify not only his or her right to speak but our own as well (potentially, inevitably), since a right made contingent for one is a right made contingent for all. And when we evince unconcern over this, either because our sentiments (for the moment) align with those of an inflamed mob or because we’re taking a strictly legalistic view, we make a mockery of the principles embedded in the First Amendment (that is, the reasons behind the rights expressed). We’re basically allowing a series of proxy wars to be waged on our very own right to free speech. And we do so, per Douglass, at our own risk: “Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist.”

Far better (both nobler and more effective) options exist for the agitated college students and the agitated suburban parents. When the occasion arises, the former can set up protests outside the venue at which the offending speech is to occur. Or the students can go inside and challenge the speaker through aggressive if respectful (that is, nondisruptive) debate, during an allotted question-and-answer session. Or they can run editorials through whatever outlets. Or they can invite speakers more to their liking to come to campus as a kind of rebuttal. Anything is better and more effective than stifling speech. And for the disgruntled suburban parents, there is the simple matter that school boards are subject to scheduled elections, such elections (at any level of government) being in essence recall elections, and the vote itself—of course—being a form of speech. Further, parents are free to run for the board themselves. Until such elections, however, many of the options available to college students are available to the parents as well: protests outside the venue, respectful if aggressive debate inside the venue, editorials, etc. Breaking up the proceedings to silence the speaker or speakers is not the answer.

Unwanted ideas don’t go away just because an unwanted speaker is chased off or an unwanted agenda is disrupted. Such ideas merely go underground, and become potentially more potent, which means we will have voluntarily sacrificed our rights for nothing.